Insight Article By Richard Miniter January 24, 1994

Summary: In the mid-1980s, collegians suddenly had to worry about being “politically correct:’ Since then, this ideal has wrapped its tentacles around campus debate, smothering free speech in the name of sensitivity. Now someone’s fighting back.

In 1991, Rep. Henry Hyde, an IlÂlinois Republican, sponsored legÂislation that would have made it easier for students at both public and private colleges to sue over First Amendment issues. The bill was inÂtended to help students who felt their right to free speech had been stifled by “PC” crusaders – liberal activists who have managed to make “political correctness” the most pressing issue on American campuses. But Hyde could find only 25 cosponsors and the bill languished. The “PC backlash” went nowhere.

Indeed, since the PC wars began in the mid-1980s with skirmishes on the canon – should Plato or Sappho be required reading – college adÂministrators have become hypersenÂsitive to the needs of women and miÂnorities. Perhaps as a consequence, arguments over what should be taught in the classroom have given way to acrimonious debate on civility – how to make students get along on campus.

Pressured by vocal groups espousÂing multiculturalism, both public and private universities have adopted speech codes directed at students and faculty. Intended at first to curÂtail incidents of “hate speech;’ usuÂally racial slurs, such codes have been extended to regulate all aspects of campus life – students have been asked to remove Confederate flags from their dorm rooms and forbidden from talking with outside journalists without permission.

Howard takes on speech codes.

“The pro bono lawyer leading the cause, John Howard, has 14 such cases pending…Once the university and its attorneys learned that the fraternity intended to make its case on constitutional grounds, the school signaled it wanted to settle.”

More importantly, while a handful of students have been disciplined for directing hateful remarks at minorÂities, others have been the victims of overzealous persecution, most notaÂbly University of Pennsylvania unÂdergraduate Eden Jacobowitz, who called a group of black sorority sisÂters “water buffalo” when their loud revelry late at night disturbed his study. Jacobowitz, who could have been expelled for falling into a common shouting match – he said his choice of epithet had nothing to do with race-received a reprieve when the women dropped their charges beÂfore disciplinary hearings were held, saying in a prepared statement that Jacobowitz and his faculty adviser “chose to circumvent the process and try this grievance among students in the national media, making it an issue of freedom of speech and politiÂcal correctness, while blanketing the real issue: racial harassment.”

But on the other side of the counÂtry, students outside the glare of the media are challenging university speech codes more methodically -in the courts, employing a new CaliÂfornia law that explicitly forbids high schools and universities, both public and private, from infringing upon students’ rights to free speech.

Known as “the Leonard law” after its sponsor, Bill Leonard, a RepubÂlican state senator from Upland, Calif., it has been the fulcrum of free speech cases at Occidental College in Los Angeles, California State UniverÂsity at Northridge and other schools. The pro bona lawyer leading the cause, John Howard, has 14 such cases pending. With state legislaÂtures across the country considering similar bills, Leonard, Howard and California students may be opening a new chapter in the history of political correctness.

Until 1993, when the Leonard law went into effect, First AmendmentÂwaving students generally lost clashes with politically correct school administrators. Then came the “T-shirt Incident;’ as a pivotal case at the University of California, Riverside, came to be known. At first, the T-shirt Incident followed the stanÂdard PC scenario: a relatively small disagreement was followed by a seÂries of administrative fiats invoking ever sterner penalties and, finally, fuÂtile campus appeals. That this parÂticular case ended with a surprising plot twist makes it a bellwether, at least for California.

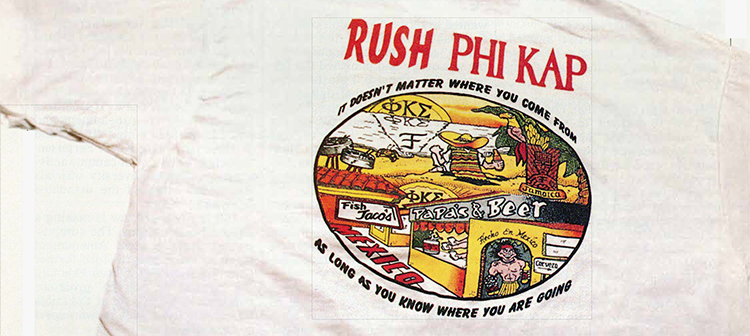

It all began in September 1993 durÂing Rush Week, when students aspirÂing to join fraternities and sororities attend parties sponsored by the local chapters. The school’s Phi Kappa Sigma fraternity was throwing a “South of the Border Fiesta,” which some brothers advertised by wearing specially printed T-shirts featuring caricatures of a sombreroed MexiÂcan toting a bottle and a bare-chested Indian hefting a six-pack and a bottle.

The shirt caught the attention of more than party-hearty freshmen. The campus chapter of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan, a HisÂpanic student group, became very inÂterested in the event. (MEChA, “the Chicano Student Movement of AzÂtlan,” takes its name from the mythÂical word for the land comprising Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, CaliforÂnia and other areas that the founders of the national group believe ought to be returned to Mexico.) Where camÂpus revelers saw adolescent humor,

MEChA saw painful stereotypes. Mario Martinez, director of external affairs for the campus MEChA chapÂter, told the Press-Enterprise, a local newspaper, that the shirt constituted fighting words and could provoke vioÂlence from Hispanic students.

“You and I could look at that TÂshirt and say, ‘What’s the big deal?’ ” says Jack Chappell, a university spokesman. “But for someone from another background, it could cut them to the quick.”

In the weeks that followed, no sanction seemed stern enough for Phi Kappa Sigma – critics and friends alike called for harsh punishments. Even the fraternity’s national headÂquarters recommended a program of contrition to the judiciary committee of the university’s Interfraternity Council; that plan was accepted and imposed. Each member of the fraterÂnity was to perform at least 16 hours of community service in a Chicano or Latino area by the end of 1993; each member was to attend two multiculÂtural awareness seminars that year; and the chapter was to write formal letters of apology to MEChA and to the rest of the sororities and fraterÂnities on campus. (National fraterÂnity organizations frequently side with PC crusaders out of self-interest and accommodation, but some of the national offices have caught a bit of the PC bug themselves. An officer at Phi Kappa Sigma national headquarÂters told the Los Angeles Times that it recommended the sanctions beÂcause it “felt that the chapter was frankly kind of stupid for not realizÂing people could be offended.”)

The university judiciary commitÂtee added a few punishments of its own. It ordered the fraternity to deÂstroy the offending shirts and barred the group from campus intramural sports for one year. It also tried to ban Phi Kappa Sigma from rush activÂities, but the Interfraternity Council overruled that.

Still, MEChA was not satisfied. The group pushed to have the local chapter of Phi Kappa Sigma disbanded – and it convinced the administration of the justice of its cause. Vincent Del Pizzo, the school’s assistant vice chancellor, dissolved the chapter for at least three years, calling the T-shirt Incident “the last straw.”

Del Pizzo defended his action by citing 14 violations of school rules by Phi Kappa Sigma stretching back to 1984, when the fraternity showed the

X-rated movie Debbie Does Dallas in a university lecture hall. (Del Pizzo’s list of violations is somewhat misÂleading, considering that most of the current fraternity brothers were in junior high or high school when the infractions occurred.) University spokesman Chappell maintains that Phi Kappa Sigmas were known as “hell-raisers on campus;’ and adminÂistrators in general felt that the fraÂternity’s penchant for outrageous beÂhavior was “picking up steam in the past 24 months.” (It is difficult to comÂpare Phi Kappa Sigma to Animal House because the fraternity does not have a house and must use univerÂsity facilities for its events.)

The fraternity brothers offered a number of arguments in their own defense. For one thing, they said, the shirt featured an antiracist slogan drawn from the lyrics of a song by the late Jamaican musician Bob Marley: “It doesn’t matter where you come from as long as you know where you are going.” Also, the shirt’s design was drawn by two Hispanic members of the fraternity. Besides, says RichÂard Carrez, the chapter president, Phi Kappa Sigma is more diverse than the campus as a whole, or any other campus group. Of its 40 memÂbers, more than one-third are HisÂpanic; others are Asians and Jews. (MECh A, by contrast, doesn’t have a single non-Hispanic member.) FiÂnally, there’s the fraternity’s motto: “Strength Through Diversity.”

The university wasn’t swayed. Says Chappell, “Having Hispanic members does not inoculate them” from the charge.

Faced with dissolution, Phi Kappa Sigma decided to sue. With Howard’s help, they took their case to Riverside County Superior Court. In response, the university emÂployed the classic legal gambit-“adÂministrative remedy” – which stipÂulates that campus groups seek internal solutions to problems before turning to outside venues. The fraterÂnity had the option to appeal Del PizÂzo’s decision to the campus board of review, for example, but Phi Kappa Sigma never did so. “It is a typical strategy,” says Howard, but state law does not require students to adhere to the policy of administrative remÂedy.

Although Howard himself was never in a fraternity, his employer, the Los Angeles-based Individual Rights Foundation, has been very active deÂfending Greek-letter organizations from campus persecution. Oddly enough, the foundation was the brainÂchild of David Horowitz and Peter Collier, two former left-wing radicals who moved into the conservative colÂumn in the late 1970s. “In the sixties, they were fighting against the univerÂsity for free speech. They still are,” says Maura Whalen, the foundation’s communications director.

By providing much of the legal basis for defending fraternities’ free speech rights, the Leonard law is preserving a peer support group 11that provides aid and comfort to kids with mainstream views:’ says attorney John Howard. Fraternities and sororities provide a refuge for students anxious to escape a politically correct campus culture.

Once the university and its attorÂneys learned that the fraternity inÂtended to make its case on constituÂtional grounds, the school signaled it wanted to settle. “We didn’t consider the T-shirt Incident in that context before,” says Chappell. Significantly, the university had punished the fraÂternity for offensive T-shirts in the past, including one that depicted a skeleton making an obscene gesture. Never before, Chappell says, did the fraternity raise the issue of free speech. “All that means,” says HowÂard, “is that the kids didn’t know they had rights.”

Constitutional rights aside, the university had another reason to setÂtle quickly – money. The Leonard law allows the court to award legal fees. “If it went to trial it could have cost more than $100, 000;’ says HowÂard.

In fact, the Leonard law is “one of the greatest things ever devised by any politician anywhere;’ says HowÂard. Until 1993, high schools and colÂleges were considered “limited pubÂlic forums;’ communities somewhere between town squares, where all opinions are allowed expression, and private homes, where owners are free to banish dissenters. A longtime advocate of free speech and individÂual rights, Bill Leonard decided to change all of that.

The Leonard law forbids all high schools and colleges, public and priÂvate, from abridging the free speech rights of their students. Free speech rights are defined as those rights spelled out in the First Amendment to the U. S. Constitution and Section 1\vo of Article One of the California Constitution. The intent of the law is best captured in Section 4, subsection 8 (b): “A student shall have the same right to exercise his or her right to free speech on campus as he or she enjoys when off campus.” (Religious schools that are controlled by bona fide churches are exempted from the law, but only in cases where free speech would in fact conflict “with the religious tenets of the organiÂzation.”)

By providing much of the legal baÂsis for defending fraternities’ free speech rights, the Leonard law is preÂserving a peer support group “that provides aid and comfort to kids with mainstream views;’ says Howard. Fraternities and sororities, which ofÂten have substantial off-campus supÂport, provide a refuge for students anxious to escape a politically corÂrect campus culture. Campus adminÂistrators, Howard says, tend to see fraternity members as “beer swilling vulgarians” who represent “centers of white, male, heterosexual priviÂlege.”

In negotiating the settlement of Phi Kappa Sigma’s lawsuit, Howard agreed to surrender his fee if univerÂsity administrators would attend a First Amendment seminar. “It is havÂing much of the effect I wanted;’ he says of the Leonard law. “It sensitizes them to the First Amendment and how it limits their power.” (By the end of 1993, Del Pizzo; Kevin Ferguson, the school’s director of campus activÂities; and other university officials still hadn’t ·attended the mandated seminar.)

But the Leonard law is making a difference on campus. The adminisÂtration plans a First Amendment teach-in which may feature former CBS News President Fred Friendly, the Edward R. Murrow professor emeritus of journalism at Columbia University and a well-known expert on free speech.

The lawsuit also means changes for the campus minority groups. They will have to realize, says ChapÂpell, they “can’t rely on the governÂment to take up the cudgel on their behalf.”